Heat Pumps in Multi-Family Buildings

Decarbonizing our cities is one of the key challenges of our time. To achieve climate targets and end our dependence on fossil fuels, we need to fundamentally change the way we heat our buildings. While individual solutions are already established in rural areas, the urban heat transition poses a particular challenge—but there are also many examples of successful implementation.

The Urban Challenge

Cities are complex. Dense development, different types of buildings, complicated ownership structures, and sometimes limited outdoor space for heat sources make decarbonizing urban heat supply a challenging task. In addition, the building stock in cities is predominantly old – in most European countries, 52-60 percent of multi-family buildings were built before 1970, long before the first energy standards were introduced.[1]

The building sector plays a significant role: in Europe, buildings account for around 40 percent of total energy consumption and 36 percent of CO₂ emissions.[2] Successful decarbonization of cities is therefore inconceivable without a transformation of the heat supply in buildings.

Nevertheless, there is good news: the technological solutions already exist. It is no longer a question of “if,” but of “how” – which solution is suitable for which type of building.

Municipal heating plans play a crucial role in the successful implementation of the urban heating transition. They create the necessary planning security for building owners and enable coordinated, neighborhood-based development of the heating infrastructure. The heating plans form the strategic basis for making optimal use of available heat sources and network structures, thereby efficiently advancing the decarbonization of cities.

Different Building Types – Different Solutions

In cities, there are essentially three types of buildings, each suited to different heat pump solutions:

Detached existing buildings: Decentralized heat pumps are very well suited for these buildings, as already described in episodes two and five of this series. Each building receives its own heat pump, which can be tailored to specific requirements. In Germany, a total of 365,000 heat pumps were sold in 2023, 85 percent of which were installed in existing buildings – clear proof that the technology is also being accepted in older buildings.[3]

Very dense inner-city development: In the densely built-up centers of our cities, decentralized solutions often reach their limits. There is a lack of space for individual outdoor units, geothermal probes, or groundwater wells. The solution here lies in district and local heating with large, central heat pumps.

These large heat pumps can achieve outputs of several megawatts and use heat sources that would not be accessible to individual buildings: river water, purified wastewater from sewage treatment plants, waste heat from industrial processes, or even deep geothermal energy. The big advantage: a single well-planned system can supply thousands of households without the need for structural measures in each building.

One impressive example is MVV’s 20 MW large-scale heat pump in Mannheim, which uses river water from the Rhine as a heat source to supply thousands of households with climate-friendly heat.[4] The Rhine water is cooled by just a few degrees and returned to the river – a closed cycle with no negative environmental impact. This plant saves around 10,000 tons of CO₂ annually.

Another pioneering example comes from Stuttgart, where EnBW operates a large heat pump with a capacity of 7 MW that uses treated wastewater from the sewage treatment plant as a heat source.[5] The wastewater has temperatures between 10 and 20°C all year round, making it an ideal, constantly available heat source. The plant can heat the equivalent of up to 10,000 households and shows how urban infrastructure can be used intelligently for the heat transition.

These district heating solutions with large heat pumps are particularly suitable for densely built-up inner-city neighborhoods, where investing in a heating network makes economic sense and where individual building solutions would reach their limits. They also make it possible to decarbonize historic city centers without the need for costly renovations to each individual listed building.

Multi-Family Buildings (MFBs): For this category of buildings—which accounts for a significant proportion of the urban building stock—there are a variety of heat pump solutions ranging from fully centralized to decentralized concepts.

Multi-Family Buildings: A Variety of Solutions

MFBs account for a significant proportion of the urban building stock – 48 percent of the European population lives in them.[6] Their successful decarbonization is therefore crucial to the success of the urban heat transition.

The good news is that there are numerous successful examples from across Europe that show that heat pumps work in MFBs – both in new and existing buildings. The variety of solutions is remarkable and allows a suitable answer to be found for almost every situation.

Three Real Life Innovations

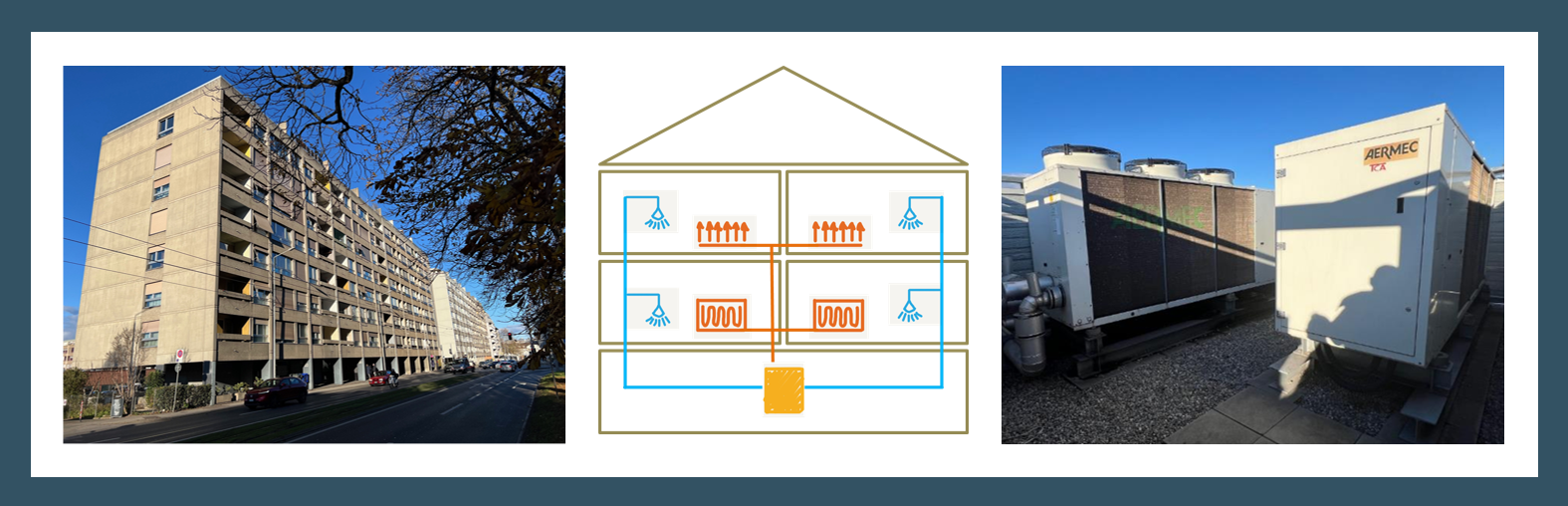

1. St. Julien, Geneva: Heat Pumps in an Unrenovated Old Building

A project in St-Julien near Geneva impressively demonstrates that heat pumps also work in poorly insulated buildings.[7] The 53-apartment building (4,049 m²), built in 1972, was equipped with two industrial air-to-water heat pumps (156 kW each) – without any changes to the existing radiators. As the work was carried out exclusively on the roof and in the basement boiler room, the residents did not have to leave their apartments during the construction phase.

The backup oil boiler that was originally planned proved to be redundant and was removed after two years. The most important finding: Even in non-renovated buildings, it is possible to install heat pumps in apartment buildings. The key factors are proper planning and dimensioning, as well as a well-considered control system for all components.

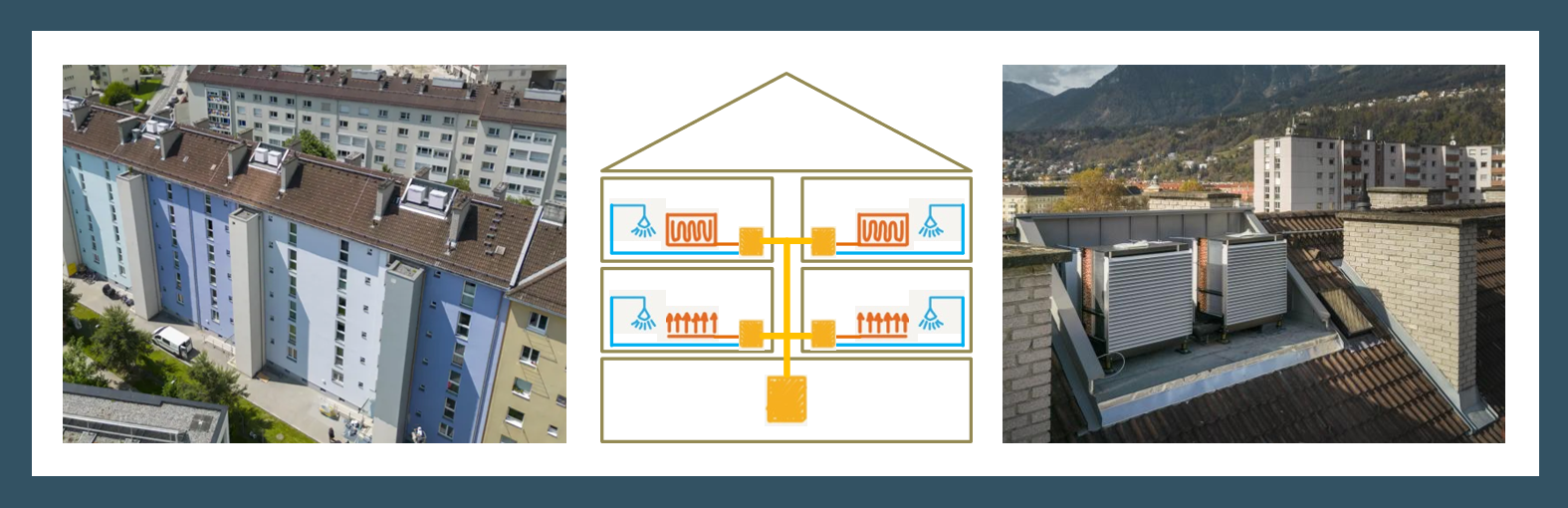

2. Fennerstrasse, Innsbruck: Mini Heat Pump with Central Supply

A particularly innovative approach was implemented in Innsbruck: 48 apartments were equipped with a hybrid system consisting of a central heat pump installed on the roof, which distributes energy at a flow temperature of only 20°C, and individual 3 kW mini heat pumps in each apartment, which raise the temperature for heating and domestic hot water (DHW).[8]

The system achieves an overall efficiency (SCOP) of 4.0 with an operating noise level of only 38 dB. The low supply temperature significantly reduces circulation losses. A key advantage is that the installation can be carried out without the residents having to move out, and the mini heat pumps work directly with existing radiators.

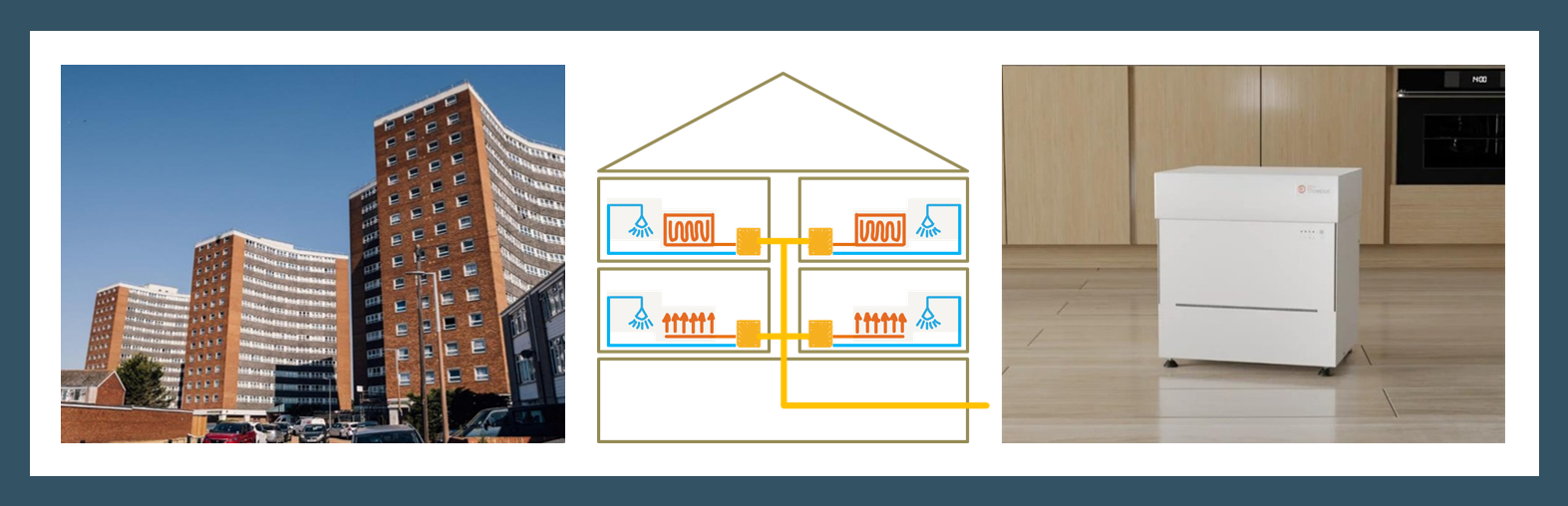

3. Chadwell St Mary, United Kingdom: Individual Heat Pumps with Common Geothermal Source

A fully decentralized system with a shared heat source is being implemented in three high-rise towers with 273 apartments.[9] Each apartment has its own compact geothermal heat pump (3-6 kW) connected to a shared geothermal probe field. The geothermal probes transfer ambient temperatures (-5°C to 20°C) to a shared circuit from which each heat pump draws energy individually.

The system achieves a coefficient of performance of 3.8 and reduces energy costs by 40 to 50 percent—particularly important for residents threatened by energy poverty. The projected CO₂ reduction is over 70 percent. This so-called “fifth generation district heating” solution[10] also offers opportunities for utilizing waste heat and free passive cooling.

Systematic Approach Instead of Individual Cases: Understanding Diversity

These three examples show very different approaches—and that is no coincidence. The diversity of MFBs and their conditions makes it necessary to offer different solutions. In order to structure this diversity, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has developed a systematic classification as part of two projects (Annex 50 and the subsequent Annex 62).

The solutions can be divided into five main categories according to the degree of centralization – from fully centralized systems for the entire building to combined approaches to individual solutions for each apartment or even individual rooms. The spectrum ranges from a single central heat pump supplying the entire building (as in St. Julien) to hybrid centralized-decentralized systems (as in Innsbruck) to fully decentralized concepts with individual heat pumps per apartment (as in Chadwell St Mary).

Each of these solution categories has its specific advantages and disadvantages. Centralized systems are often easier to maintain and can use larger, more efficient heat pumps, but they have higher distribution losses. Decentralized systems minimize distribution losses and allow individual control, but they require more equipment and can cause noise problems with air source heat pumps. Choosing the right solution depends on many factors: building size, energy standard, available heat sources, ownership structure, and budget.

In the case of centralized solutions, container solutions are also increasingly being offered by many suppliers on the market. These prefabricated, modular units contain the complete heat pump technology, including controls, and can be installed quickly and with little construction effort. They offer the advantage of protected installation, reduced on-site assembly times and enable flexible scaling of the heating output by combining several modules.

The practical guide for heat pumps in MFBs published by the German Energy Agency (dena) emphasizes the importance of a systematic approach and offers specific recommendations for the planning, installation, and operation of heat pumps in different types of multi-family buildings.[11]

Conclusions: The Path to Urban Heat Transition

First things first: Heat pump systems in MFBs are technically feasible and are increasingly being implemented throughout Europe and other regions.

Successful implementation requires careful adaptation: technical solutions must be tailored to the specific characteristics of the building. Whether centralized, decentralized, mono-energetic, or hybrid, it depends on many factors (size of the building, energy standard, available heat sources, etc.) and must be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Technical solutions exist for virtually all multifamily building contexts: the diversity of successfully implemented projects shows that there is a suitable heat pump solution for almost every situation. The technology is mature and adaptable for various urban multi-family applications. At the same time, more standardization is needed in the future to speed up processes and thus reduce costs.

Broader implementation requires more than just technology: non-technical barriers, such as financing and approval mechanisms, must be addressed. The transition to heat pump systems in MFBs is not only a technical challenge, but also a complex socio-technical transformation that requires coordinated efforts across the entire building sector.

The future belongs to Multi-Family Buildings

As Europe moves toward climate neutrality, the systematic implementation of heat pumps in apartment buildings will play an increasingly critical role in achieving decarbonization goals—while ensuring comfortable and affordable housing for all residents.

The urban heat transition is no longer a distant vision, but a real possibility that is already being implemented in numerous projects today. The variety of solutions available makes it possible to find a suitable answer for almost every MFB – from centralized large-scale systems to decentralized individual solutions.

The key to success does not lie in searching for the one perfect solution – because there is no such thing. Instead, it is about understanding the variety of options available and finding the right solution for each specific building. The examples presented and the systematic classification are intended to help navigate this path.

In a Nutshell

Decarbonizing our cities is feasible. The technology is available, the examples are numerous, and the findings from practical experience are encouraging. What is still missing is widespread implementation—and that begins with the certainty that it works.

This article is part of our comprehensive series answering the 18 most important questions about heat pump technology. The series is organized into 6 thematic categories. Below you’ll find more articles from the same category, as well as the complete navigation to all other topics.

Real-World Performace

Field studies, efficiency measurements, and proven results. 20 years of data from 840+ installations in all building types.

Episode 2: 20 Years of Field Studies Prove: Heat Pumps Efficient in Existing Buildings

20 years of field research monitoring 840+ heat pumps in existing buildings. Latest studies show average efficiency (SPF) of 3.4 – even with radiators.

Episode 5: Efficiency Knows no Age: Heat Pumps in Buildings from 1826 to Present Day

6 case studies from 1826-1995: Unrenovated historic buildings achieve SPF 3.5-5.1 with proper planning and hydraulics.

Episode 6: Heat Pumps in Multi-Family Buildings: The Key to Urban Decarbonization

100+ documented cases prove heat pumps work in apartment buildings worldwide – centralized systems to individual units.

Foundations & Context

Why heat pumps matter for society, climate, and energy transition. Understand the big picture through social context, myth-busting, environmental impact analysis, and policy evaluation.

Episode 1: Beyond the Noise: What the Heat Pump Truly Means for Our Society

Why heat pumps are the fastest, most cost-effective path to energy independence – beyond political noise and fossil fuel myths.

Episode 4: The Heat Pumps Fact Check: Ten Myths Scientifically Disproven

Ten persistent myths scientifically debunked: heat pumps work in extreme cold, historic buildings, and with existing radiators.

Episode 17 (coming soon): Ecological viewpoint

Heat pumps reduce CO₂ emissions by 60-90% compared to gas heating. An environmental analysis.

Episode 18 (coming soon): Are Heat Pump Goals Achievable?

Achieving ambitious heat pump targets: Analysis of technical feasibility, economicviability, and political requirements for climate-neutral heating by 2045.

Technology & Systems

How heat pumps work, different system types, technological evolution, and refrigerant technology. From 20 years of progress to safety of natural refrigerants.

Episode 3: From Niche to Norm: 20 Years of Progress in Heat Pump Technology

Modern heat pumps: 10-15 dB quieter, 20% more efficient, and work up to 70°C—perfect for retrofits.

Episode 7: Hybrid Heat Pump Systems

Analysis reveals: Pure electric heat pumps outperform fossil hybrids in 95% of cases—lower costs, higher efficiency.

Episode 11: Between Air Conditioner and Heating System

Air-to-air heat pumps: lower installation costs, faster deployment, but different comfort level than water-based systems. Systemic comparison.

Episode 12: Heating Technologies Compared

Comprehensive comparison of all heating technologies: heat pumps, gas, hydrogen, biomass, and district heating – pragmatic decision framework.

Episode 16 (coming soon): Refrigerants

Refrigerant evolution: From R410A to natural refrigerants – environmental impact, safety, and efficiency of modern solutions.

Economics & Costs

Operating expenses, installation costs, and long-term financial analysis. Real data on savings, price trends, and return on investment.

Episode 8: Operating Costs: Heat Pumps Already Outperform Gas Heating Systems Today

Save €400-1000/year compared to gas heating today – savings rise to €2,270/year by 2035. Interactive calculator included.

Episode 13: Heat Pump Installation Costs: Germany vs. Europe

German heat pump installations cost €20,000-40,000 – twice the European average. Analysis reveals why and what must change.

Planning & Implementation

Selecting, installing, and optimizing heat pumps for your needs. Practical guides from system sizing to installer selection.

Episode 9: Thousands of Heat Pumps Models on the Market: How to Find the Right One for Me?

Navigate 10,000+ certified heat pump models: Step-by-step guide from heating load calculation to installer selection and system commissioning.

Smart Integration

AI optimization, solar integration, and intelligent energy management. Next-generation heating systems that learn, adapt, and maximize efficiency.

Episode 10: Heat Pumps and AI: A Perfect Match?

AI-controlled heat pumps boost efficiency by 5-13%, reduce costs 40%, and support grid flexibility—research proven.

Episode 14: HEMS: Intelligent Control for Heat Pump Systems

Smart home energy management systems optimize heat pump operation, reduce costs by 15-25%, and enable grid services.

Episode 15: Heat Pumps as Energy Systems

How, with the help of PV, battery storages and electric cars, heat pumps become efficient complete systems. Analysis on savings, own production and bidirectional charging

[1] Miara, M. (2022). Heat Pumps in Multi-Family Buildings for Space Heating and Domestic Hot Water (Final Report Annex 50, Report no. HPT-AN50-1). Technology Collaboration Programme on Heat Pumping Technologies (HPT TCP), S. 14-15.

[2] European Climate Foundation (ECF). (2022, März). The Building Emissions Problem. Accessible via: https://europeanclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/ecf-building-emissions-problem-march2022.pdf

[3] D. Günther et al., „WP-QS im Bestand: Entwicklung optimierter Versorgungskonzepte und nachhaltiger Qualitätssicherungsmaßnahmen für Wärmepumpen im EFH-Bestand,” Fraunhofer-Institut für Solare Energiesysteme ISE, Freiburg, Abschlussbericht, Okt. 2025.

[4] Siemens Energy. (o.J.). MVV Mannheim: Großwärmepumpe für klimafreundliche Fernwärme. Accessible via: https://www.siemens-energy.com/de/de/home/stories/mvv-mannheim.html

[5] EnBW. (o.J.). Großwärmepumpe liefert Fernwärme für 10.000 Haushalte. Accessible via: https://www.enbw.com/presse/grosswaermepumpe-liefert-fernwaerme-fuer-10-000-haushalte.html

[6] Eurostat. (2024). Housing in Europe — interactive publication [Interaktive Publikation]. Accessible via: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/de/web/interactive-publications/housing-2024

[7] Technology Collaboration Programme on Heat Pumping Technologies (HPT TCP). (o. J.). Case studies: St. Julien, Geneva, Switzerland [Projektseite Annex 62]. Accessible via: https://heatpumpingtechnologies.org/project62/case-studies-1/

[8] Vaillant Group. (2023). taking care Magazine 2023 (S. 60–63). Remscheid, Germany: Vaillant Group. Accessed on 30.11.2025 via https://www.vaillant-group.com/newsroom/publications/2023/taking-care-magazine-2023/tcm22_d_20230419.pdf

[9] Kensa Contracting. (o. J.). Chadwell St Mary Ground Source Heating [Case Study]. Accessed on 30.11.2025 via https://kensa.co.uk/social-housing/case-study/chadwell-st-mary-ground-source-heating

[10] Buffa, S., Cozzini, M., D’Antoni, M., Baratieri, M., & Fedrizzi, R. (2019). 5th generation district heating and cooling systems: A review of existing cases in Europe. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 104, 504-522.

[11] Deutsche Energie-Agentur GmbH (dena). (Hrsg.). (o. J.). Praxisleitfaden für Wärmepumpen in Mehrfamilienhäusern: Status quo. Erfahrungen. Möglichkeiten. Berlin, Germany: dena.